Four outstanding smiths will have gems coming across the block.

The annual auction of American Bladesmith Society knives to support the continuing programs of the ABS is a highlight of the BLADE Show, and 2024 will be another memorable year when the hammer comes down at the Cobb Galleria Centre in Atlanta.

Once again, ABS master smith Brion Tomberlin is handling the logistics of the pre-auction process. He has brought together a roster of four outstanding ABS bladesmiths for this year’s event, and his appreciation of the ABS and what it means is reflected in his recent years of dedication to the auction.

“The ABS means so much to everyone involved and to the legacy and future of bladesmithing,” Brion commented. “It has developed so many bladesmiths through the years and helped to carry on the traditions and methods that have been used for generations. At the same time, it has brought along a younger group that will help keep interest in the forge alive and prospering.”

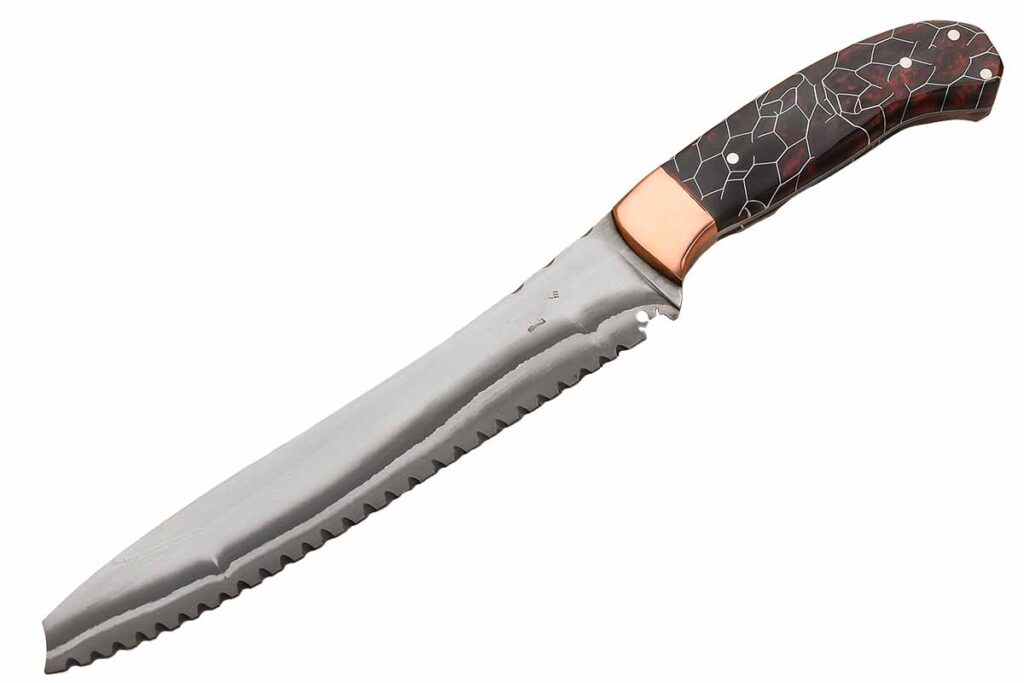

Long Clip-Point

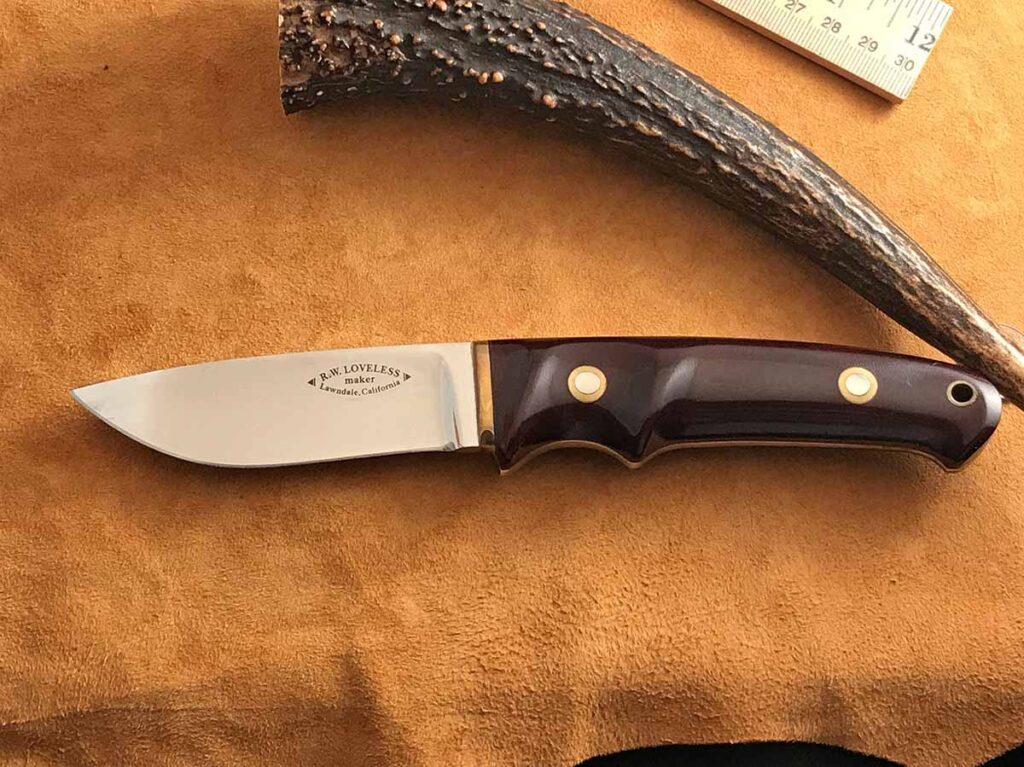

Jonathan Caruso of Conway, Arkansas, has been an ABS member for nine years now and earned his ABS journeyman smith rating at BLADE Show ’22. He will provide a long clip-point hunter with a single guard for the auction and to showcase his talent. “I chose this style of knife for the purpose of use,” he commented. “Although the knife was designed to be eye-catching, all my knives are created to be used for the tasks they were created for, which in this case is a functional hunting knife.”

Caruso adds that his goal with his ABS contribution knife is to deliver form and function with “a nice appeal, much like an evening gown or a cocktail dress.” He has added the flair and visual appeal of a hamon—essentially the line of demarcation where the hardened cutting edge and the softer spine converge on the blade—using a technique he learned from ABS master smith Jim Crowell. “It’s a process dubbed a ‘flame-painted hamon,’” Jonathan explained. “Instead of using the traditional clay method to create the hamon, I use an oxyacetylene torch to heat the cutting edge before hardening. I chose this method because I wanted to incorporate what I’ve learned from a very well-known master smith who has taught me a wealth of knowledge about bladesmithing and the history of the ABS.”

Caruso’s clip-point hunter features a 6-inch blade of W2 tool steel, sculpted guard of 416 stainless steel with vulcanized red and black spacers, and a handle of stabilized black walnut from Knife & Gun Finishing Supplies. Overall length: 11 inches.

“I chose the W2 to get a more definitive differentially heat-treated appeal,” Jonathan noted, “and the black walnut handle because it draws the eyes in to look at its stunning details. I feel like the handle material was waiting for such a knife and such an occasion as the ABS auction to be used. The black walnut handle material was purchased from Iron Dungeon Forge at BLADE Show Texas in 2023. I finally made it over to their table late on the afternoon of the first day and couldn’t believe that this beautiful piece hadn’t been bought yet.”

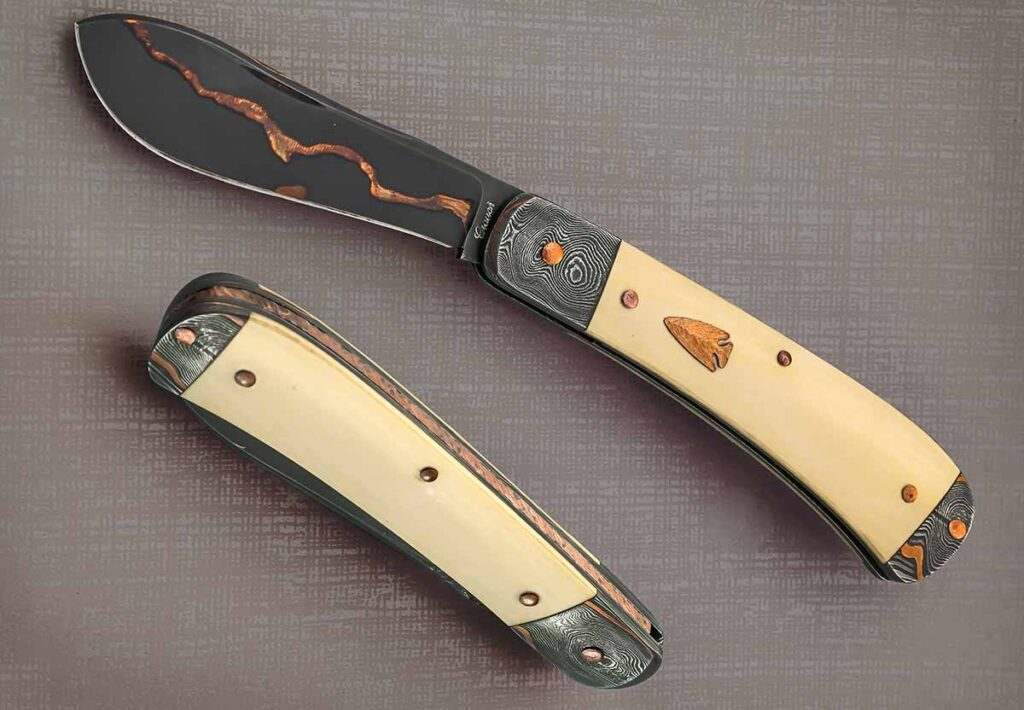

Chairman’s Trapper

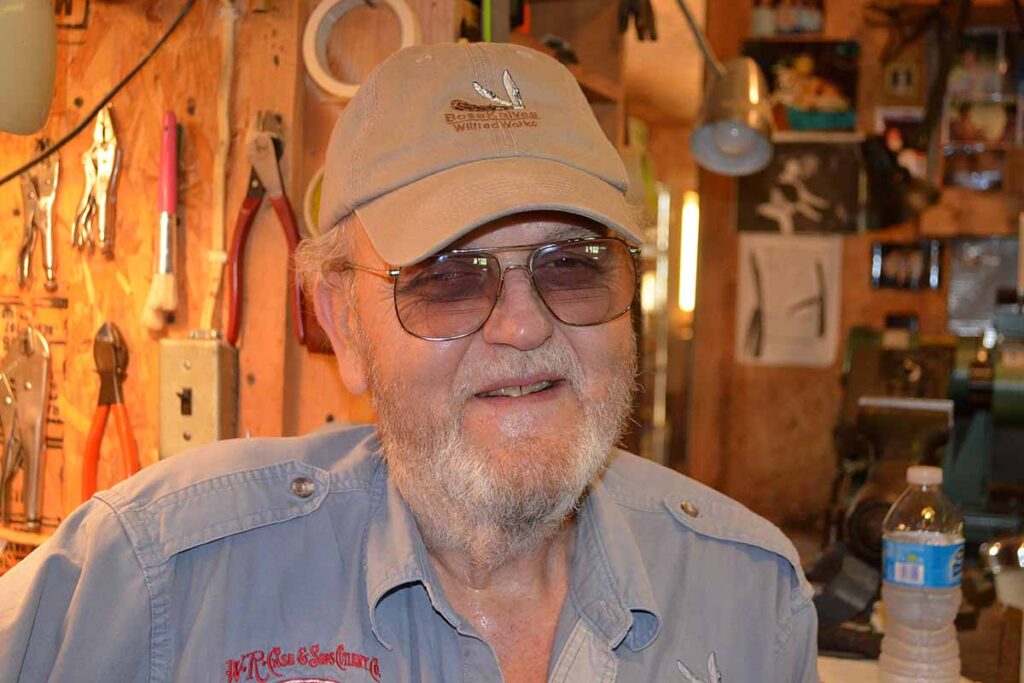

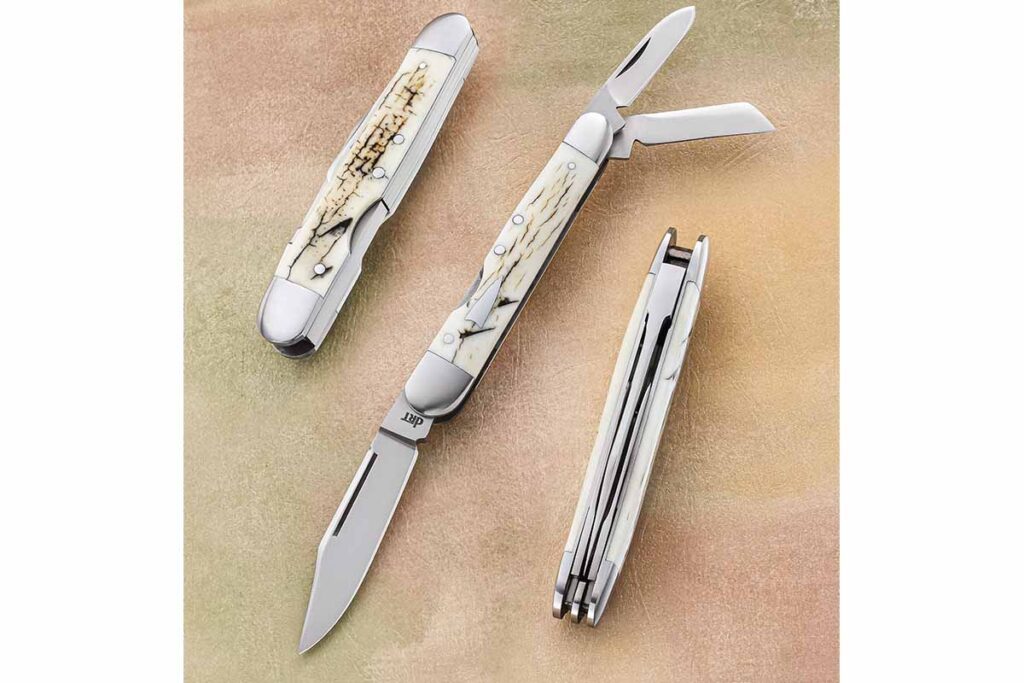

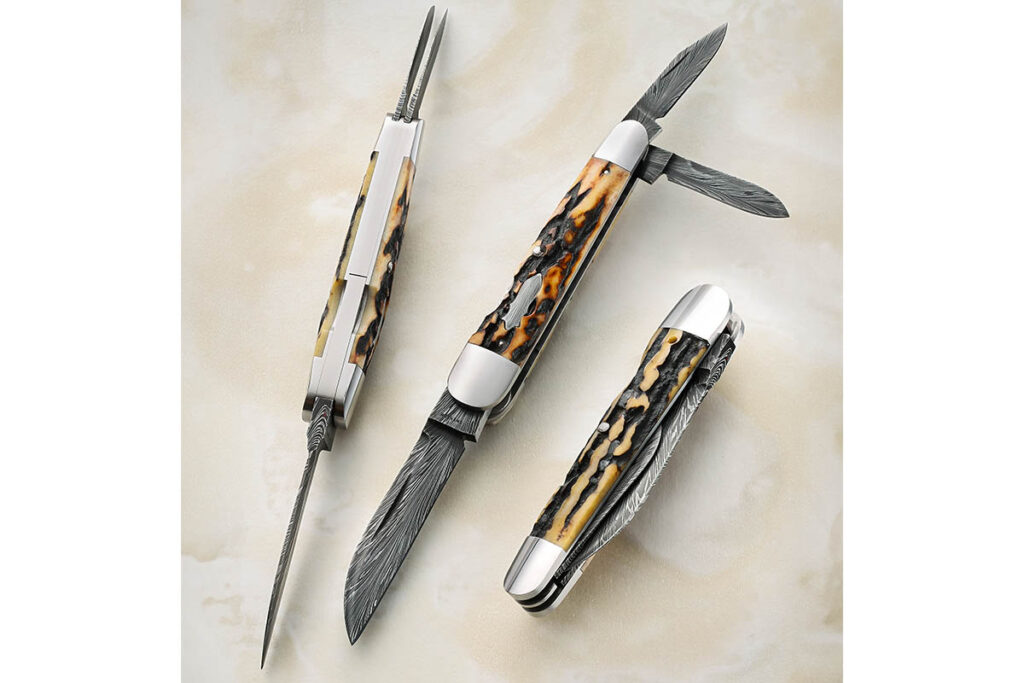

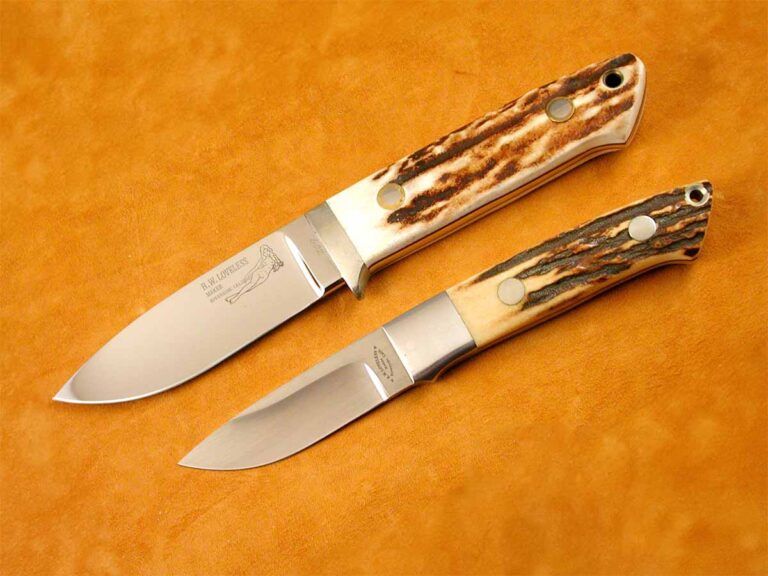

Current ABS chairman Steve Dunn has been a member of the Society since 1990, two years after he began making knives as a hobby. He became an ABS master smith in 1994 and has taught at the ABS schools regularly. He joined the organization’s board of directors in 2003 and has been a committed servant of the ABS for 34 years.

“Each year the ABS has an auction at the BLADE Show to raise money for our schools for education of the forged blade,” he remarked. “I was asked to make the master smith folder this year, and I chose to make a traditional slipjoint. The reason I chose the slipjoint is that most everyone carries some kind of pocketknife—mostly slipjoints, I would think.”

Dunn’s contribution to this year’s ABS auction is a single-blade trapper with a 3-inch blade of twisted W’s pattern damascus. The damascus is a combination of 1075 carbon and 15N20 nickel-alloy steels. The bolster sports American-style scrollwork with 24k-gold inlay. The scales are sambar stag. Closed length: 3.75 inches. “The reason I chose this blade steel is that the two components contrast well together and for the edge-holding ability they offer,” Steve said.

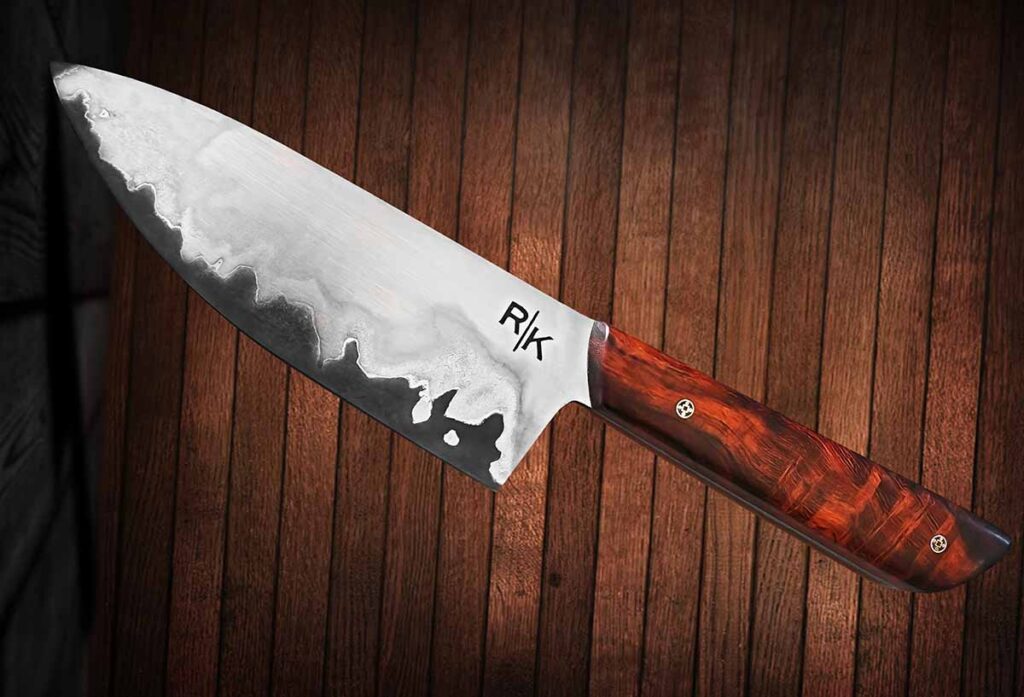

Dagger Hamon

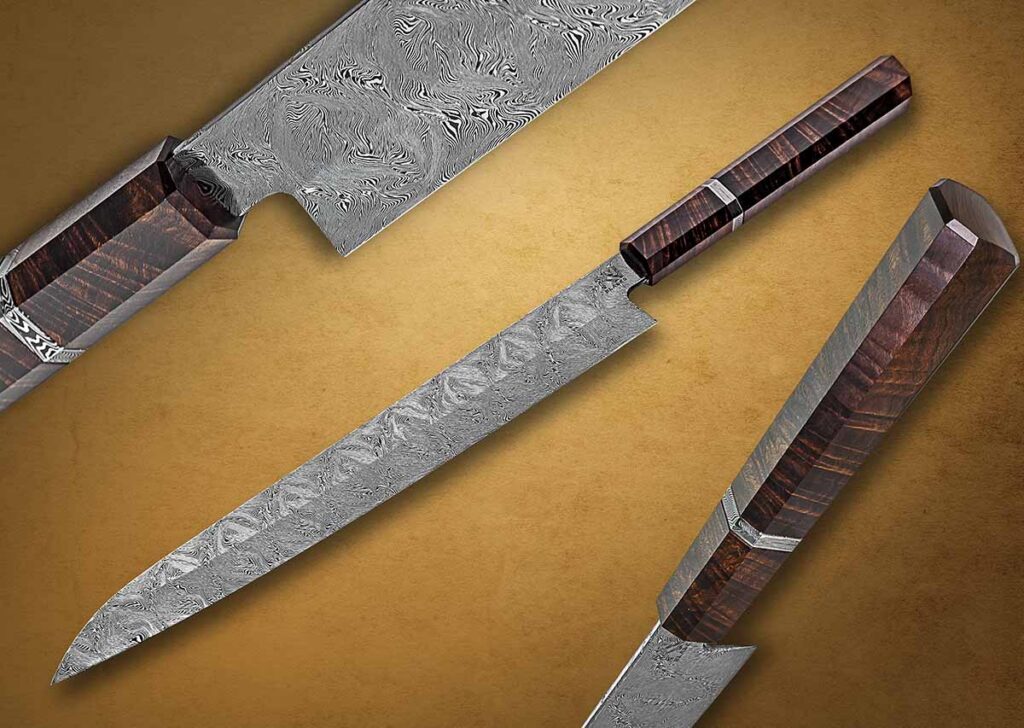

For James Rodebaugh, who joined the ABS in 1999 and received the Society’s master smith designation in 2004, the ABS is a worthy recipient of the contributions from its members to the auction each year. “Number one, the ABS is largely responsible for the high level of bladesmithing in the world today and the award winners that are recognized at the BLADE Shows in Texas and Atlanta. The ABS is always well represented when the winners are named in these shows, overwhelmingly so.”

Rodebaugh became a member of the ABS board of directors in 2014, and he sees the organization as continuing to build a future for the art of bladesmithing. Meanwhile, he is pleased to help out with the auction. “The ABS has given a lot to the knifemaking world,” he observed, “and this is my way of giving back in general.”

For the auction, James has chosen a dagger with an 8-inch blade of W2 tool steel that’s about an inch across at its widest point. The frame handle construction will feature domed silver pins and Tasmanian blackwood. James expects the overall length to be between 12 and 13 inches. An added feature is the clayed hamon.

“I don’t see many people doing a dagger with a hamon,” Rodebaugh opined, “and that used to be one of my signature things until I got away from it. I was originally going to go with damascus, but we see a lot of that, and with the finishing aspect of the work it is harder to do a properly finished carbon steel blade with a hamon than it is to etch a piece of damascus. Plus, I just like the look of the hamon. Also, the W2 steel shows a lot of action on the hamon, and it has a fairly short time and temperature curve so that the edge will harden and the thicker portion will stay soft, which gives you definition and activity on the hamon.”

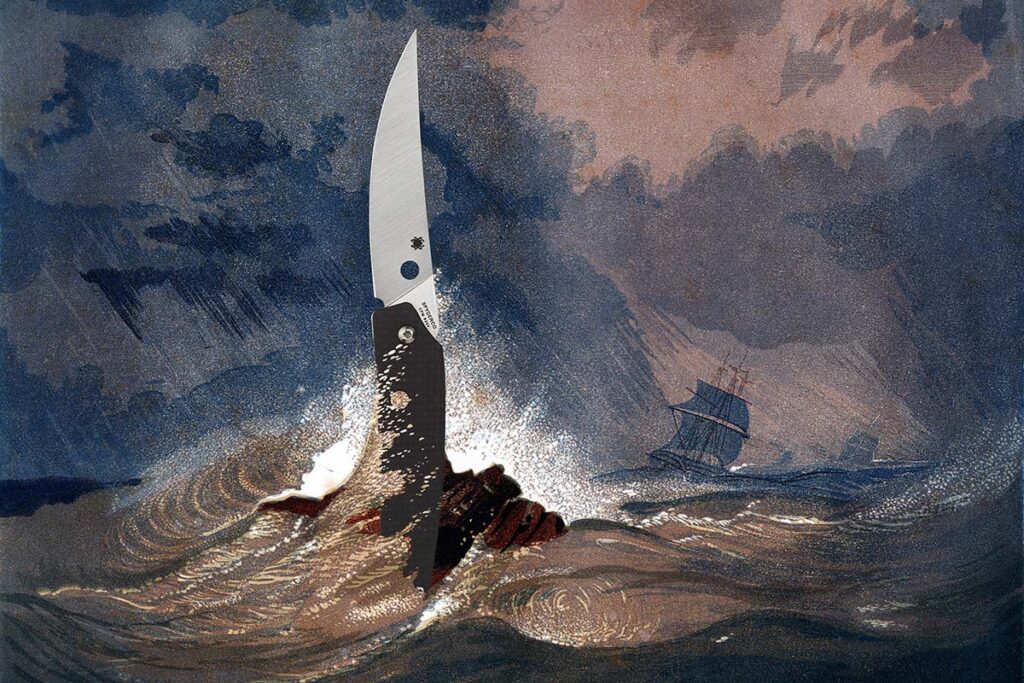

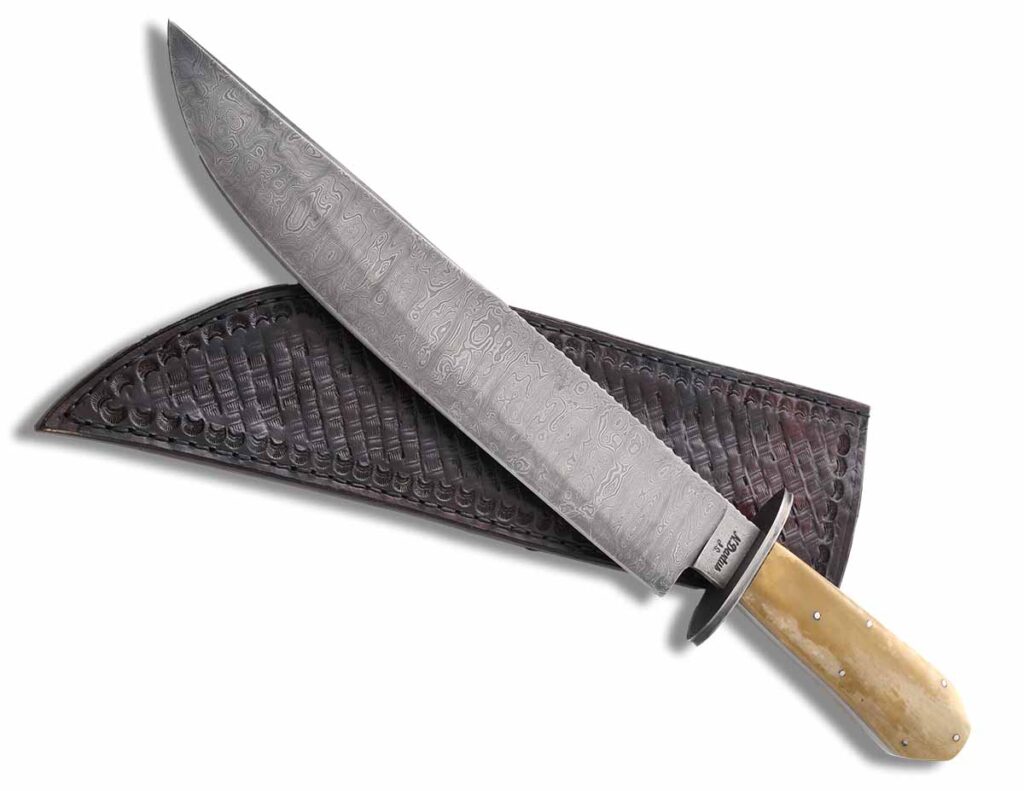

Coffin Bowie

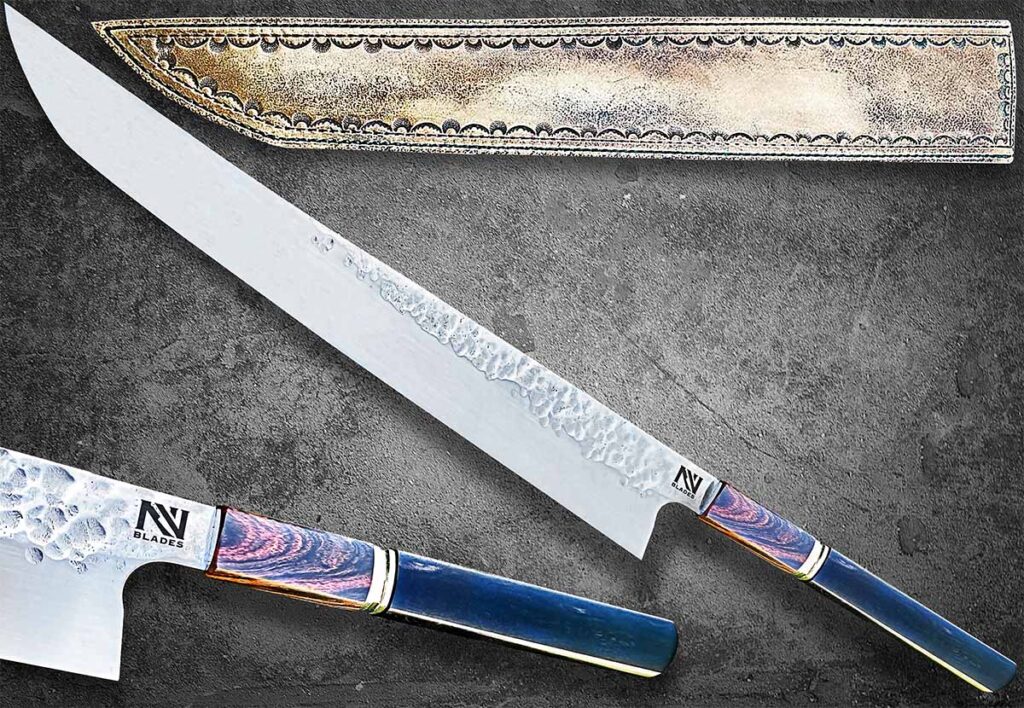

ABS journeyman smith Nicolas Dartus began forging in his shop in eastern France in 2014, joined the ABS in 2016, and received the Society’s journeyman designation at BLADE Show ’19. He is working toward his master smith goal today, and he says that it is an honor to have one of his knives included in the prestigious ABS auction.

“For the auction, I’m making a coffin bowie,” Nicolas said. “For me, the coffin bowie is a typical American knife and I love it. Of course, my eye is a French eye, and I don’t have an American interpretation for this creation, but it is my vision! I think individuals have their own styles of knives. Of course, the ABS is an American society, but its members come from all over the world with different cultures and design ideas.”

Nicolas plans to make the knife with a blade of 320-layer damascus forged from 1075 carbon and 15N20 nickel-alloy steels. The handle will be giraffe bone and the piece will be accompanied by a leather sheath. “I’ll make the knife the traditional way,” he offered. “For me, working with the ABS is a great adventure.”

When these wonderful examples of modern bladesmithing come up for sale, the bidding is liable to be as heated as any forge. Those who go home with one of these beauties will not only have the satisfaction of ownership, but also in knowing they have directly assisted the ABS, providing support for the society’s ongoing mission of excellence.