Four U.S.-based companies embrace making military knives stateside.

Make no mistake—manufacturing knives in the USA comes with challenges, including regulations, taxes, high costs of doing business and much more. While imported knives often beat American-mades on price, companies that choose to produce knives domestically carry a long tradition of equipping the U.S. military with the best American design and manufacturing has to offer.

Spartan Blades

For Curtis Iovito, with Mark Carey co-founder of Spartan Blades, the tension between creating high-quality knives and keeping costs down has been one of the primary challenges in running Spartan for the past 13 years.

“We did everything we could to keep our costs down, from buying in bulk, streamlining production and reducing shipping costs,” Curtis observed. “Even with that, we were lambasted by our customers for being ‘too expensive.’ It was our No. 1 complaint. We even received hate mail for it!”

For Iovito—who said those who staff Spartan Blades consider themselves soldiers first and knifemakers second—patriotism was among the top reasons to make knives in Southern Pines, North Carolina, despite the challenges of starting a manufacturing venture there. Another reason is the ability to have fine control over the deadlines and the manufacturing process, he added. That control and the pursuit of quality it allows has enabled Spartan Blades to make knives for special operations forces, the FBI, U.S. Marshals Service and “every other three-lettered group out there,” Iovito said.

Located on the backside of Fort Bragg, Spartan Blades has plenty of soldiers stopping by to shop, though there are many who do not have enough money to take home one of the company’s top-tier Gold Line knives. “Every single packing list I have ever seen for a soldier has ‘fixed blade knife’ listed on it,” Iovito said, “and most of the time the soldiers are required to acquire it themselves.”

Consequently, Spartan began offering two other grades of knives. The Bronze Line is manufactured in Taiwan and the Silver Line, also known as Pineland Cutlery, is a collaboration between Spartan and KA-BAR to create a more affordable line in the latter’s facility in Olean, New York. The Alala is the first result of that collaboration.

“We wanted to make a knife that was lightweight, easy to carry and that could be carried on airborne operations,” Iovito said. The Alala is made suitable for airborne operations by focusing a good deal of effort on developing a hard sheath with double retention. It’s been out for about a year now. It has a flat-ground 3.75-inch blade and a canvas Micarta® handle. It weighs just shy of a third of a pound and is ground from 1095 Cro-Van steel, where additional elements such as molybdenum and nitrogen make it tougher than standard 1095 spring steel. As Iovito noted, “KA-BAR has been using this steel for years and has the heat treatment down to a science.”

TOPS Knives

A couple of years ago, TOPS Knives of Ucon, Idaho, figured it hadn’t released any big combat knives in a while, so company president and knife designer Leo Espinoza developed the Operator 7.

“Like most of our knives, we have a tendency to over-build them, so we made the Operator 7 out of 5/16-inch-thick, 1075 carbon steel to ensure that the knife could literally handle anything you need it to do,” wrote Dylan Waters, dealer liaison for TOPS. The Operator 7 and its 7.25-inch blade hit the market in 2018. In October of the same year, the company released the Blackout variation of the knife: Black Traction Coating on the blade and a black synthetic handle with a red border.

There are few cutting tasks that are too large for a big combat knife, a necessity when another knife isn’t an arm’s reach away.

“In a community where a lot of the time the only gear you have is what you carried in, the choice comes down to the individual’s personal preference,” Waters said, explaining why the knife is a good carry for members of the military. “The Operator 7 Blackout Edition is a very capable blade and it definitely has its place in the field.”

For the company known for its use of 1095, TOPS reached for 1075 steel for this project because it better resists impact and sharpens easily. Even the Micarta/G-10 combo handle helps aid in big cutting jobs. “The G-10 is on the bottom layer to help with impact because it is harder than Micarta,” Waters explained, “and the Micarta is on the top layer to help with grip.”

Every TOPS knife save one design is manufactured at its Idaho shop, and the company brain trust sees little advantage to manufacturing anywhere else. “We are a U.S. company supporting other U.S. companies by sourcing materials from them,” Waters pointed out. “Sure, sometimes prices are higher compared to sourcing overseas but when it is all said and done, the end user has peace of mind that they are getting quality product that they can trust.”

Though the U.S. military announced it is working toward leaving Afghanistan after about 20 years fighting terrorism there, the need for a good quality knife will continue, as the military is constantly training and preparing just in case, Waters said. And if things do go south, TOPS will “rest assured that these soldiers will have tools that are purpose-built and won’t fail when they need them the most.”

Bear & Son Cutlery

From the shipyards near Mobile to missile and rocket development in Huntsville, Alabama plays a big role in the nation’s space and military programs. Sitting amidst the state home to Fort Rucker and Maxwell Air Force Base is Bear & Son Cutlery, which takes pride in creating knives for customers that include troops and government contractors.

“We are one of only a handful of knife manufacturers in the United States, and the largest in the Southeast,” said Matt Griffey, company vice president. “Also, we’re a family-owned and operated business, something less common nowadays.”

Bear & Son has long manufactured knives with an eye toward people in uniform. For instance, the company first released a version of the Bear Tac CC-110-B4-B design using D2 tool steel and a Micarta handle back in 1999, a couple of years before 9/11 shifted the nation’s perception of what threats stood against it.

When Bear & Son launched its Bear Ops line in 2011, it brought the knife back because it liked the design with its “strong tip, full tang, solid handle material, non-reflective, easy to sharpen steel, and adaptable sheath,” Griffey observed. In a 1095 spring steel blade with an epoxy powder coat and a G-10 handle, the knife is 10.375 inches overall. The accompanying Kydex sheath is jump ready, meaning not only does the sheath hug the knife in place, it also has a snap for extra security.

Bear & Son makes the knife at its shop in Jacksonville, Alabama, a place where Griffey says members of the community quickly produce knife designs with pride and quality they can control. “A major advantage of keeping our Alabama factory in operation is providing families a career or skill they can be proud of,” Griffey said. “Understanding our products and services positively impact the lives of our friends, family and neighbors is worth the regulations and taxes of operating in the United States.”

For instance, students at a nearby state university gain real-world experiences at Bear & Son. Meanwhile, some Bear craftspeople and designers have 20-plus years of experience working with numerous types of steels and can develop client orders in a timely manner, Griffey noted.

While the mission of the nation’s military may change, the mission at Bear & Son continues to “provide quality made products that service personnel can depend on,” Griffey said. “The market for strong, reliable blades will be steady, though we will see some trends in sizes, shapes and materials move around.”

Winkler Knives

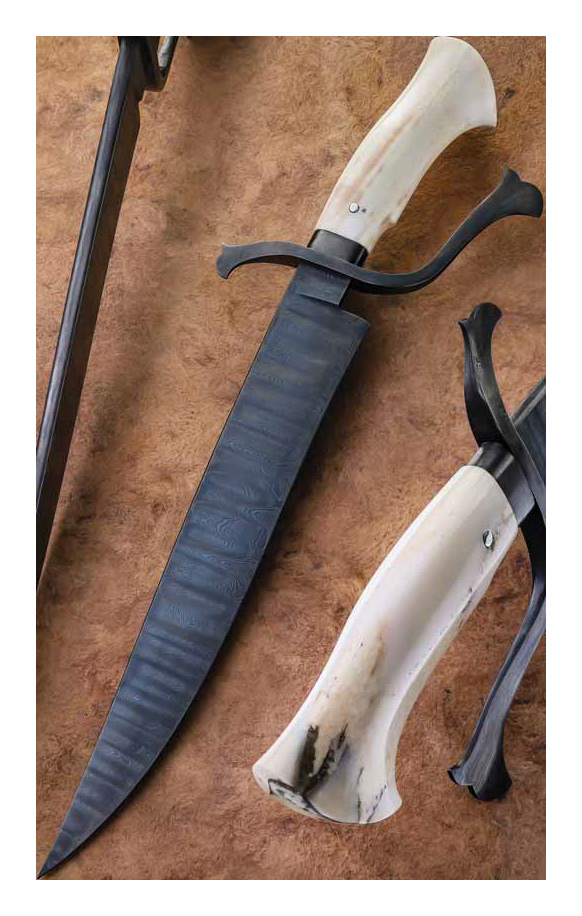

Daniel Winkler of Winkler Knives in Boone, North Carolina, readily admits that if you’re looking for a knife to take camping, his WK Tactical Dagger is not for you. With a 5.5-inch blade and short bevels the dagger has little utility use, he noted, beyond the thing knives can do when the enemy is close. “The design was a collaboration between me and one of the Army special operations team leaders,” he said. “It was a design they needed for their specialized type of fieldwork.”

The 80CrV2 carbon steel offers “the best consistent performance” of any steel Winkler works with, and the blade sits nestled in a lined, Boltaron sheath. “The handle shape does not hang on clothing as a lot of cross-guard knives do,” he noted. “The handle shape also gives good indexing and a flair to assist in removal leverage after use.”

The primary goal of Winkler Knives is to provide tools to first responders, law enforcement and the military, Daniel said, and most of its knives and other edged tools go to people working in those fields. He added that running a company in the USA allows Winkler Knives complete control over the tools it makes, thus ensuring consistency and quality.

Despite the taxes and other challenges of manufacturing domestically, Winkler said, “The advantage is we live in the greatest country on Earth. Taxes and regulations are sometimes tough but still better than any alternative I can see. We have been very fortunate to find great staff.”

When hiring people, Winkler usually passes over knifemakers as he wants to train workers to make the edged tools his way. Some of the folks working there have backgrounds in foodservice and construction fields. Staff must work well in the team and have integrity, he added.

Most design work is kept in-shop too, as most Winkler Knives customers are seeking out Winkler designs. In the end, Daniel does all his manufacturing for his military customers in the USA. As he concluded, “I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Get More Knife Info:

- Four Battle Tough Military-Style Fixed Blade Knives

- Chute Knife: Full-Spectrum Warrior

- What U.S. Military Members Look for in a Knife

- Edged-Weapon Expert Talks Knife Fighting